18、天遒谷西

305 2021-03-08 00:38:55

回复: [转载]原神怪物血量直观表,外加各种环境血量加成测量数据[v1.3,2.4] (4 篇回复,发表在 提瓦特军机处)

三.后话

本帖引用了不少数据,本来需要个人测量,实在太困难,血量是分段的,要测出大量数据才能实证。外加上怪物种类繁多,一时没有进展。后来偶然发现解包网,一下把进程推进了很多,但苦于没有详细到每一级的数据,我对非整五的测量出现了误差,导致我无法肯定环境加成倍数, 还把大雪猪王倍数给弄错了 ,这里要感谢@tesiacoil的及时指出 。此外,我开始并没有注意到活动里的冰树和无相基础血量改变,刚开始写上了1.6倍加成,但直到我精确测量的时候一直在1.57左右,后来才意识到应该是基础血量发生变动,特意翻了代码发现 11qq。

还有一个有趣的是,纯水会因为卡bug可以直接射箭射中本体。比如可以看一下这视频BV1Qy4y1H712

还有一个是在测量69级圣遗物本时,我把五个副本都测了是1.2倍加成,唯独冰本没有测,最后竟然发现69级冰本没有加成 !。。

(结果发现我果然又是在测血量 ,当年植物大战僵尸2的时候的新活动也是最先测量的一批。)

306 2021-03-08 00:38:31

回复: [转载]原神怪物血量直观表,外加各种环境血量加成测量数据[v1.3,2.4] (4 篇回复,发表在 提瓦特军机处)

二.正文

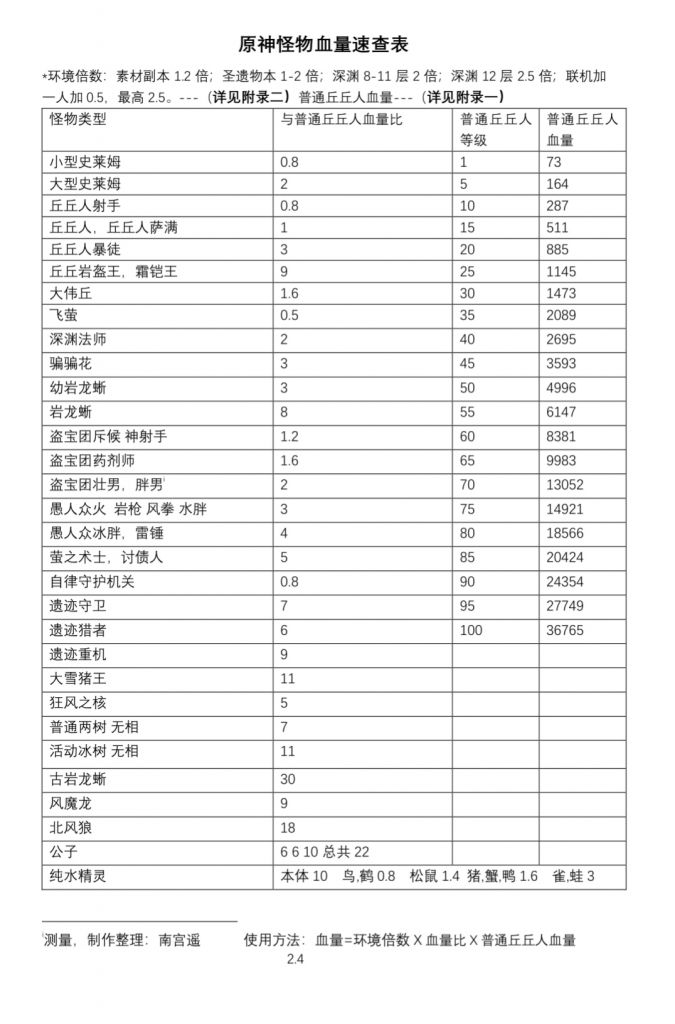

1.原神怪物血量直观表

2.附录一:丘丘人血量详表

按照此表可能会出现较小的误差,因为血量都含有小数。(如果倍数有几十,误差就可能在两位数)

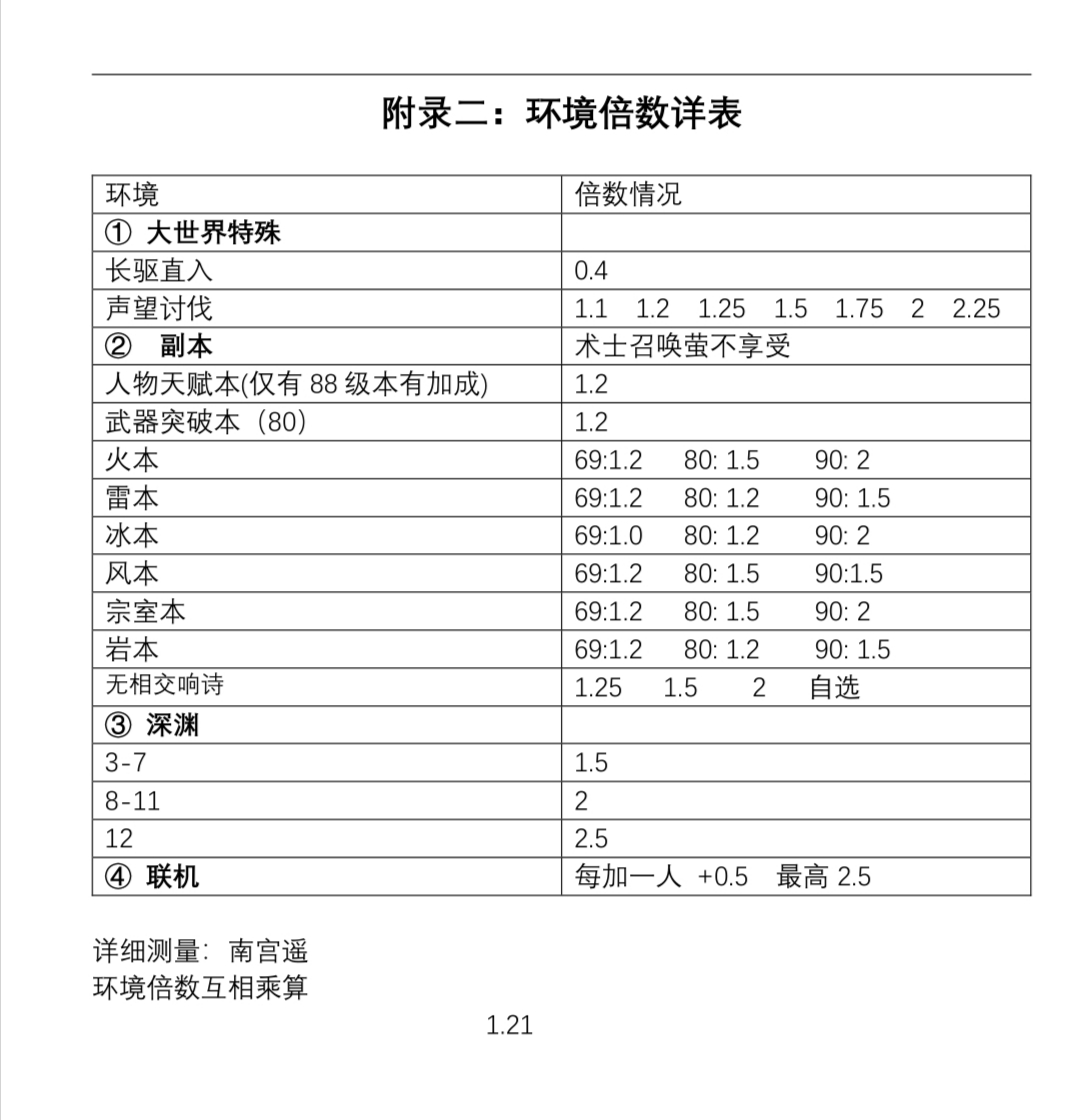

3.附录二:环境倍数详表

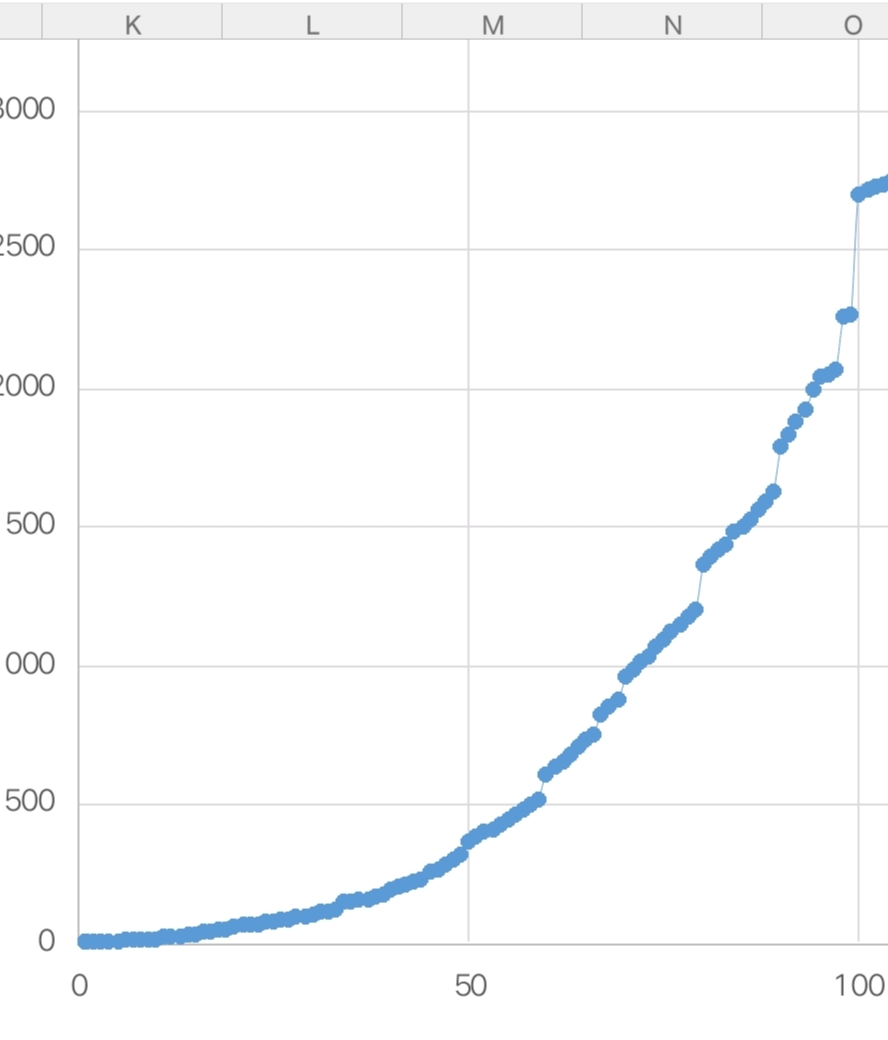

4.血量成长直观

307 2021-03-08 00:37:25

回复: [转载]原神怪物血量直观表,外加各种环境血量加成测量数据[v1.3,2.4] (4 篇回复,发表在 提瓦特军机处)

更新日志:

V1.2:

1.22发帖

V1.3

2.4更新了1.3新怪物,改进了排版

一.前言

怪物血量与同等级丘丘人存在一定量的比,这些比值是精确比,因此我在做表时无须把所有的怪的等级对应血量标出来,这样反而不够直观。(好像有人已经做过比较简单的表 。)

308 2021-03-08 00:33:03

主题: [转载]原神怪物血量直观表,外加各种环境血量加成测量数据[v1.3,2.4] (4 篇回复,发表在 提瓦特军机处)

323 2021-03-07 22:04:30

主题: [攻略]和氏锄地路线图(2021.3.11) (23 篇回复,发表在 提瓦特军机处)

路线总览:

1、孤云阁右路

2、瑶光滩右路

3、瑶光滩左路

4、星荧洞窟山上

5、乌库

6、雪葬之都近郊

7、地中之盐岩盔王

8、无妄坡山路

9、西岛岩盔王

10、奥藏山矿洞

11、奥藏山上

12、庆云顶飞岩龙蜥

13、奥藏山东岩盔王

14、绝云间东北岩盔王

15、绝云间西南丘丘

16、南天门

17、天遒谷北

18、天遒谷西

19、灵矩关

20、岩层巨渊直飞

21、天衡山西岩盔王

22、天衡山北

23、风龙废墟风核

24、望风山地

25、雪山北丘丘【NEW!】

324 2020-10-31 02:38:36

回复: 梦轩随录:王年一《大动乱的年代》河南人民出版社1988 (9 篇回复,发表在 新梦轩)

P43:

毛泽东3月下旬的谈话,重要精神之一是反对“右派”,一些工作组按照自己对“右派”的理解,过分严重地打击了向党委、向工作组发难者。毛泽东主张“横扫一切牛鬼蛇神”,一些工作组把有这样那样问题或所谓“问题”的同志看成“牛鬼蛇神”而加以打击。毛泽东号召批判所谓“反动学术权威”,一些工作组就狠狠打击所谓“反动学术权威”。

------------

工作组的“精神分裂”在此进一步加剧。现实情况是,毛的意见无人愿意反对,因此,承载着刘、邓路线和任务的工作组也不得不寻求毛语录的支持。但是,正如造反派不堪承受毛的理想一样,工作组在这一面上也如此不堪,以致他们只能互扣帽子,把毛的理想当成纯粹的战术武器。

325 2020-10-21 22:10:47

回复: 梦轩随录:王年一《大动乱的年代》河南人民出版社1988 (9 篇回复,发表在 新梦轩)

P37:

6日晚,工作组开会,认为漂上来一批“闹事”的“尖子”,出笼一批牛鬼蛇神,要组织队伍追根子。这就是“六·六”事件。事件发生后,刘少奇、陶铸要人民日报社写一篇社论揭露“假左派、真反革命”,陈伯达不同意。7日、8日、9日三天,全校各系对“尖子”开了大小斗争会,并把学生李世英等人戴上高帽子游校。9日中午,李世英自杀,未遂。后来,毛泽东称李世英为“学生领袖”。

------------

发生这样的事,无怪毛泽东在群众心中的地位如此崇高!